Recent breakthroughs in atmospheric modeling are fundamentally reshaping our understanding and prediction of global weather patterns and climate change. At the heart of this revolution lies the Coriolis effect, a phenomenon driven by Earth's rotation, whose influence on atmospheric turbulence and convection is now being integrated into next-generation parameterization schemes. This development, unfolding across leading meteorological centers worldwide, promises unprecedented accuracy in forecasts and climate projections.

Background: The Invisible Hand of Earth’s Rotation

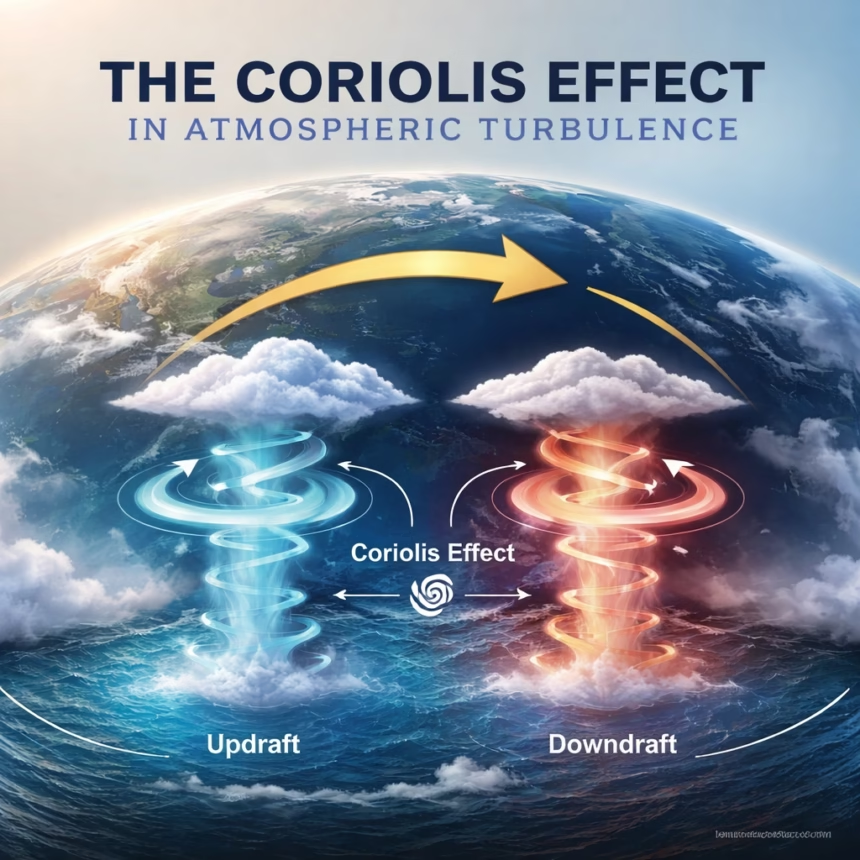

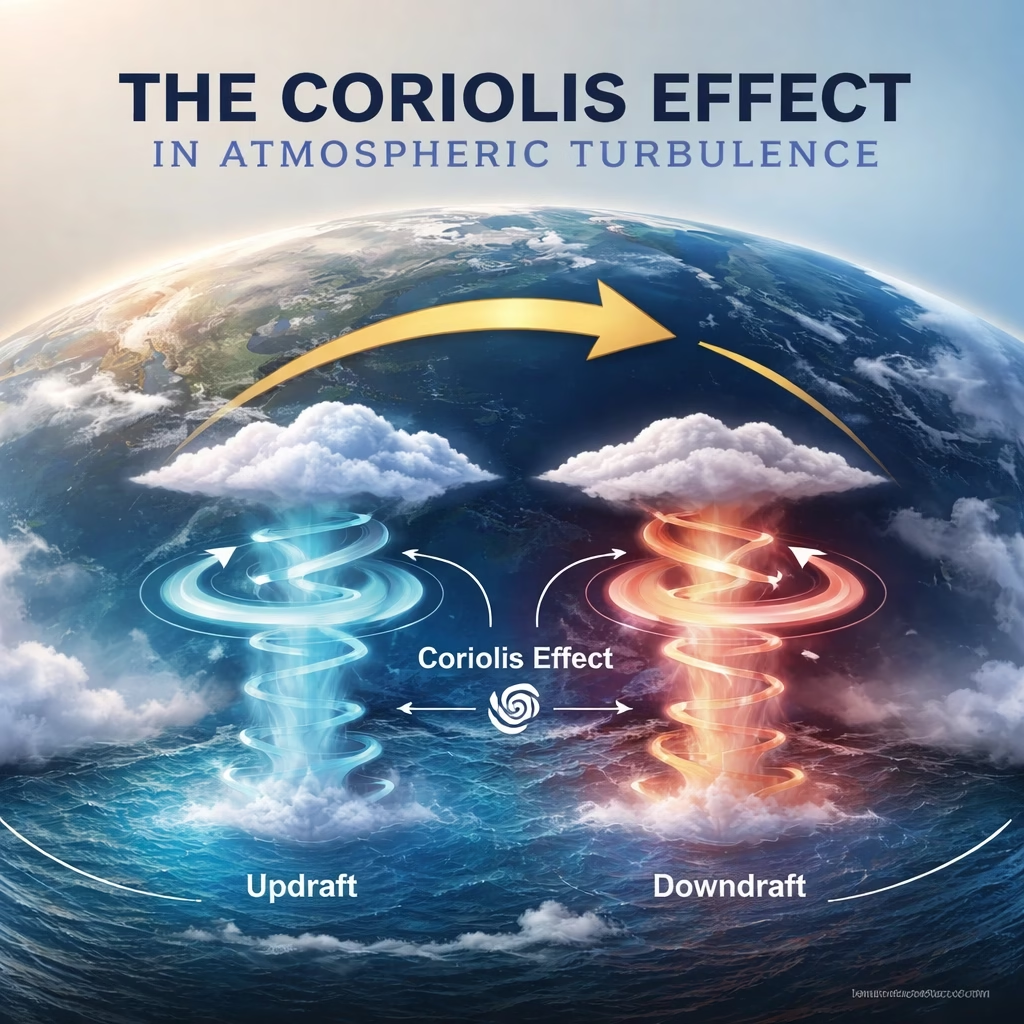

The Coriolis effect, first described by French mathematician Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis in 1835, is an inertial force that deflects moving objects on a rotating frame of reference. On Earth, this force is responsible for the large-scale spiraling of hurricanes, the direction of ocean currents, and the general pattern of global wind systems, deflecting motion to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere.

For decades, atmospheric scientists have grappled with the challenge of representing complex atmospheric processes within computational models. Global weather and climate models operate on a grid, and many crucial phenomena, such as individual clouds, thunderstorms, and fine-scale turbulence, occur at scales smaller than the grid cells. These "sub-grid scale" processes must be "parameterized"—approximated using mathematical formulas based on the larger-scale variables the model can resolve.

Historically, the Coriolis effect was primarily considered significant for large-scale atmospheric circulation, influencing weather systems spanning hundreds or thousands of kilometers. For smaller-scale phenomena like turbulent eddies or individual convective updrafts, its direct influence was often deemed negligible and thus excluded from their parameterizations. Early models, developed from the 1960s onward at institutions like the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), focused on capturing the dominant atmospheric dynamics, often simplifying or omitting intricate sub-grid interactions. This simplification was largely driven by computational limitations and a prevailing scientific consensus that the Coriolis force's timescale of action was too long to significantly impact fleeting turbulent or convective events.

Key Developments: Unveiling Micro-Scale Coriolis Impacts

A paradigm shift began in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, fueled by exponential increases in computational power and the development of "convection-permitting" and "large-eddy simulation" (LES) models. These high-resolution models, capable of resolving atmospheric features down to meters or tens of meters, started to reveal that the Coriolis effect was not always negligible at scales previously thought too small.

Researchers observed that even individual deep convective plumes, especially those that persist for extended periods or occur within strongly rotating environments (like supercells), exhibit subtle but significant rotational characteristics influenced by the Coriolis force. For instance, the formation of mesocyclones within thunderstorms, which are precursors to tornadoes, is intrinsically linked to rotational dynamics that can be influenced by the background Coriolis force, even if indirectly. Similarly, organized mesoscale convective systems, which can span hundreds of kilometers, demonstrate large-scale rotational signatures that are clearly Coriolis-driven and impact their propagation and longevity.

New parameterization schemes are now being developed and implemented to explicitly account for these effects. One crucial area is the "rotational effects in deep convective plumes," where models are incorporating terms that reflect the tendency of rising air parcels to acquire angular momentum due to the Coriolis force. Another advancement involves considering "helical turbulence," where the three-dimensional structure of turbulent eddies is influenced by rotation, affecting how momentum, heat, and moisture are transported vertically within the atmospheric boundary layer.

This re-evaluation extends to the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL), the lowest part of the atmosphere. Over large spatial domains, the Coriolis force significantly shapes the ABL's structure, influencing wind shear, the generation of turbulence, and the transport of pollutants. Modern parameterizations for ABL turbulence are moving beyond simple eddy-diffusivity models to include more sophisticated representations that account for rotational influences, particularly in stable boundary layers or over complex terrain. Major modeling centers, including the UK Met Office and NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL), are at the forefront of integrating these advanced schemes into their operational models, with initial tests showing improved skill in forecasting wind profiles and cloud formation.

Impact: Sharper Forecasts, Clearer Climate Insights

The integration of the Coriolis effect into sub-grid parameterizations is having a profound impact across meteorology and climate science. The most immediate benefit is demonstrably improved accuracy in operational weather forecasts. Better representation of convective organization leads to more precise predictions of severe weather events, including the intensity and track of tropical cyclones, the location and timing of heavy rainfall from thunderstorms, and the spatial distribution of damaging winds. For example, recent model upgrades at the ECMWF have shown a measurable increase in skill for predicting precipitation accumulations over 24-hour periods, directly attributable to refined convective parameterizations.

Beyond daily forecasts, the implications for climate projections are equally significant. Accurate parameterization of convection and turbulence is vital for correctly simulating the Earth's energy budget, hydrological cycle, and cloud feedback mechanisms—all critical components of climate sensitivity. By better capturing how heat, moisture, and momentum are redistributed vertically and horizontally within the atmosphere, climate models can produce more reliable projections of future temperature changes, regional precipitation shifts, and the frequency of extreme weather events under different climate scenarios. This provides policymakers and communities with more robust information for adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Specific sectors are already benefiting. The energy sector relies on accurate wind forecasts for renewable energy generation, and enhanced boundary layer parameterizations provide more precise wind speed and direction predictions. Agriculture benefits from improved rainfall forecasts, aiding crop planning and water management. Aviation safety is boosted by better predictions of turbulence, while disaster management agencies gain lead time for preparing for floods and severe storms.

From Daily Forecasts to Decadal Projections

The refinement of these parameterizations is not merely an academic exercise; it translates directly into tangible societal benefits. For instance, the ability to more accurately predict the formation and evolution of mesoscale convective systems (MCSs) has a direct bearing on flash flood warnings across North America and Europe. Similarly, in regions prone to tropical cyclones, better representation of the storm's inner core dynamics, influenced by rotating updrafts, can improve intensity forecasts, a notoriously difficult challenge.

What Next: The Horizon of Atmospheric Modeling

The journey to fully harness the Coriolis effect in atmospheric parameterization is far from over. Researchers are continually refining existing schemes and exploring novel approaches. One major thrust involves developing "scale-aware" parameterizations that dynamically adjust their behavior based on the model's resolution, ensuring the Coriolis effect is appropriately handled whether the model is running at coarse or fine scales.

Further computational advancements, including the advent of exascale computing, will enable even higher-resolution global models that explicitly resolve more of these processes, reducing the reliance on parameterization. However, parameterization will always remain crucial for the truly sub-microscopic scales. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) is also emerging as a transformative force. AI algorithms are being trained on high-resolution LES data to learn complex sub-grid relationships, potentially leading to more accurate and computationally efficient parameterizations than traditional physics-based approaches. Projects like Google's DeepMind and various academic initiatives are actively exploring "machine-learned parameterizations" that could implicitly capture Coriolis effects.

Looking ahead, the development of "Digital Twin Earth" initiatives, such as those proposed by the European Space Agency, envisions creating a highly accurate virtual replica of our planet, capable of real-time monitoring and high-fidelity predictions. These ambitious projects will critically depend on the advanced parameterization schemes currently under development, including those that fully account for the Coriolis effect across all relevant scales. The next decade is expected to see the operational deployment of these next-generation models, offering an unprecedented view into the intricate workings of Earth's atmosphere and delivering actionable insights for a more resilient future. This comprehensive approach to integrating the Coriolis effect promises to unlock a new era of atmospheric predictability, enhancing our ability to navigate the challenges of a changing climate and safeguard communities worldwide.