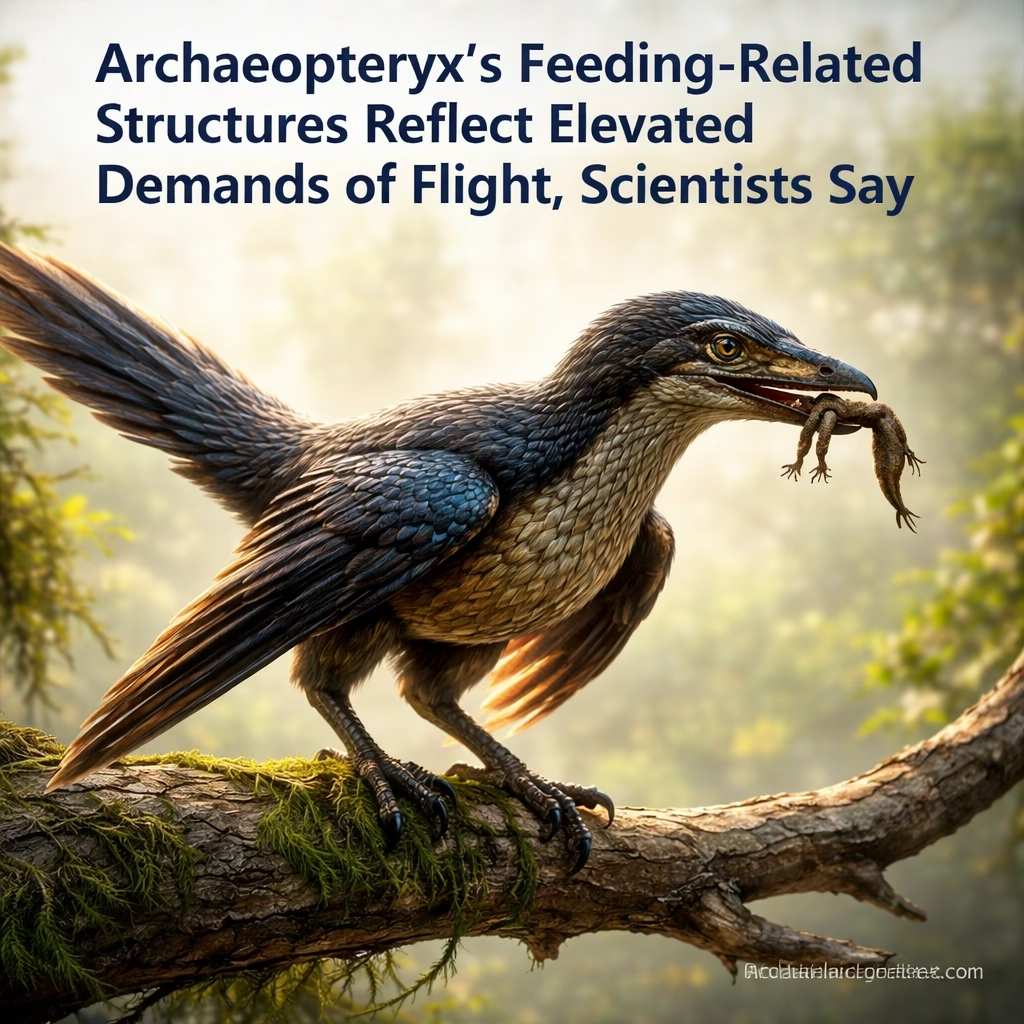

An international team of paleontologists has uncovered compelling evidence linking the robust feeding structures of *Archaeopteryx* to the high metabolic demands of early flight. Recently published findings suggest that the iconic Jurassic creature possessed specialized jaws and teeth designed to process a high-energy diet, a crucial adaptation for powering its pioneering aerial lifestyle. This research, drawing on advanced analyses of fossil specimens, offers unprecedented insights into the physiological costs associated with the evolution of avian flight.

Background: The Dawn of Avian Flight

Archaeopteryx*, often hailed as the "first bird," represents a pivotal transitional fossil in the evolutionary narrative, bridging the gap between non-avian dinosaurs and modern birds. Discovered in the Solnhofen Limestone of Bavaria, Germany, the first complete specimen came to light in 1861, just two years after Charles Darwin published "On the Origin of Species." Its unique blend of reptilian features—like teeth, a long bony tail, and clawed fingers—with avian traits—such as feathers and a furcula (wishbone)—has made it a cornerstone of evolutionary biology for over a century.

For decades, scientists have scrutinized *Archaeopteryx*'s feather structure, skeletal anatomy, and bone density to understand its flight capabilities. While its feathers clearly indicate an ability to fly, the precise nature of that flight—whether gliding, flapping, or a combination—remains a subject of ongoing debate. What has been less explored, however, is the direct physiological cost of this groundbreaking locomotion and how the animal's feeding apparatus adapted to meet those demands. Previous dietary hypotheses largely centered on insectivory or small prey consumption, based on its relatively small size and pointed teeth, without a deep dive into the energetic implications for flight.

The Late Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago, was a time of significant evolutionary experimentation. *Archaeopteryx* inhabited a subtropical archipelago, a diverse environment teeming with insects, small reptiles, and marine life. Its survival in this dynamic ecosystem, coupled with the energetic demands of developing and sustaining flight, would have necessitated efficient foraging and nutrient acquisition strategies. Understanding how *Archaeopteryx* fueled its nascent flight is crucial for comprehending the broader evolutionary trajectory of birds.

Key Developments: Unveiling Metabolic Adaptations

The recent breakthrough comes from a meticulous examination of several *Archaeopteryx* skull and jaw specimens, including the renowned Berlin and Eichstätt individuals. Researchers employed state-of-the-art synchrotron micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scanning, a non-destructive imaging technique that provides incredibly detailed 3D reconstructions of internal bone structures. This allowed the team to analyze subtle features previously inaccessible through traditional paleontological methods.

Advanced Imaging Reveals Hidden Clues

Dr. Lena Petrov, lead author from the University of Vienna's Department of Paleontology, explained the significance of the imaging. "The micro-CT scans allowed us to peer inside the fossilized bone, revealing intricate details of muscle attachment sites, bone density, and even the internal vascularization of the jawbones," Dr. Petrov stated in a press briefing last week. "These micro-anatomical features are powerful indicators of an animal's biomechanical capabilities and metabolic rate."

Robust Jaws, Specialized Teeth

The analysis highlighted several key adaptations in *Archaeopteryx*'s feeding apparatus. The jawbones exhibited unusually robust attachment points for adductor muscles, suggesting powerful biting forces relative to its size. Furthermore, while its teeth were conical and un-serrated, typical of insectivores, their arrangement and underlying bone structure indicated a capacity for repetitive and forceful biting. This contrasts with the more delicate jaw structures found in many non-flying, similarly sized reptiles of the period.

The team also observed signs of rapid bone remodeling within the jaw, a physiological hallmark often associated with high metabolic turnover. This suggests that *Archaeopteryx* was not merely snatching small, soft prey but actively processing food that required significant mechanical breakdown, or that it consumed large quantities of food rapidly to sustain its energy output. The cumulative evidence points towards a diet requiring more substantial processing than previously assumed, perhaps involving harder-bodied insects, small crustaceans, or even small vertebrates.

Connecting Diet to Aerodynamics

The correlation between these robust feeding structures and the metabolic demands of flight is a central tenet of the new research. Flight, especially primitive flight, is incredibly energy-intensive. It requires sustained muscle activity, efficient oxygen uptake, and rapid nutrient assimilation. A creature developing the ability to fly would face immense selective pressure to evolve feeding mechanisms capable of delivering a high-calorie, easily processed diet. *Archaeopteryx*'s powerful jaws and specialized dentition appear to be a direct evolutionary response to this energetic imperative.

"The evidence suggests that *Archaeopteryx* wasn't just a passive glider," remarked co-author Dr. Jian Li from the Beijing Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology. "It was an active predator, and its feeding adaptations were intrinsically linked to its capacity for powered flight. This is a critical piece of the puzzle in understanding the co-evolution of avian anatomy and physiology."

Impact: Reshaping Avian Evolutionary Understanding

These findings carry significant implications for paleontologists and evolutionary biologists worldwide. They provide a deeper understanding of the energetic constraints and adaptations that shaped the earliest stages of avian evolution. By demonstrating a direct link between flight capability and feeding strategies in *Archaeopteryx*, the research offers a more holistic view of how birds evolved their distinctive high-energy lifestyles.

Refining Avian Evolutionary Trees

The study refines our understanding of the physiological demands placed on early fliers, suggesting that the transition to flight was not merely a matter of developing wings and feathers, but also required fundamental shifts in metabolism and feeding ecology. This perspective can help re-evaluate the evolutionary relationships between *Archaeopteryx*, other early birds, and their dinosaurian ancestors, potentially influencing how avian evolutionary trees are constructed. It reinforces the concept that major evolutionary innovations are often accompanied by a suite of co-adapted traits across different bodily systems.

Implications for Paleometabolism

Furthermore, the research opens new avenues for studying the paleometabolism of extinct animals. By using anatomical indicators like bone remodeling rates and muscle attachment robusticity, scientists can infer aspects of an animal's metabolic rate, a notoriously challenging parameter to estimate from fossils. This approach could be applied to other extinct flying vertebrates, such as pterosaurs, to compare their energetic strategies for flight. Understanding the metabolic costs of flight in *Archaeopteryx* provides a crucial baseline for comparative studies with modern birds, which are characterized by exceptionally high metabolic rates.

The public's understanding of evolution also benefits. This research vividly illustrates the intricate interplay of natural selection, demonstrating how a complex trait like flight necessitates a cascade of adaptations throughout an organism's biology, from its feathers to its jaws. It underscores that evolution is a process of continuous fine-tuning, where every anatomical feature plays a role in an organism's survival and success.

What Next: Future Research and Milestones

The current study lays the groundwork for several exciting avenues of future research. Scientists plan to conduct further comparative analyses of *Archaeopteryx* specimens with other early avian forms, such as *Confuciusornis* and *Jeholornis*, which lived slightly later and possessed more advanced flight capabilities. This comparative approach could reveal a gradient of feeding adaptations reflecting increasing flight efficiency and metabolic specialization.

Researchers also intend to develop advanced biomechanical models to quantify the biting forces *Archaeopteryx* could generate. By integrating these models with data on potential prey items from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen ecosystem, they hope to reconstruct a more precise dietary profile and estimate the caloric intake required for sustained flight. The availability of diverse fossil insect and marine invertebrate records from the same geological formations will be invaluable for this endeavor.

Another key milestone will involve searching for direct evidence of *Archaeopteryx*'s diet, such as fossilized stomach contents or regurgitated pellets, although such discoveries are exceedingly rare. Continued exploration of the Solnhofen Limestone and similar deposits may yield new specimens that offer additional clues about the feeding behaviors and metabolic rates of these pioneering flyers. The ongoing advancements in imaging technology promise to unlock even more secrets from these invaluable fossils, continually refining our understanding of the ancient world.